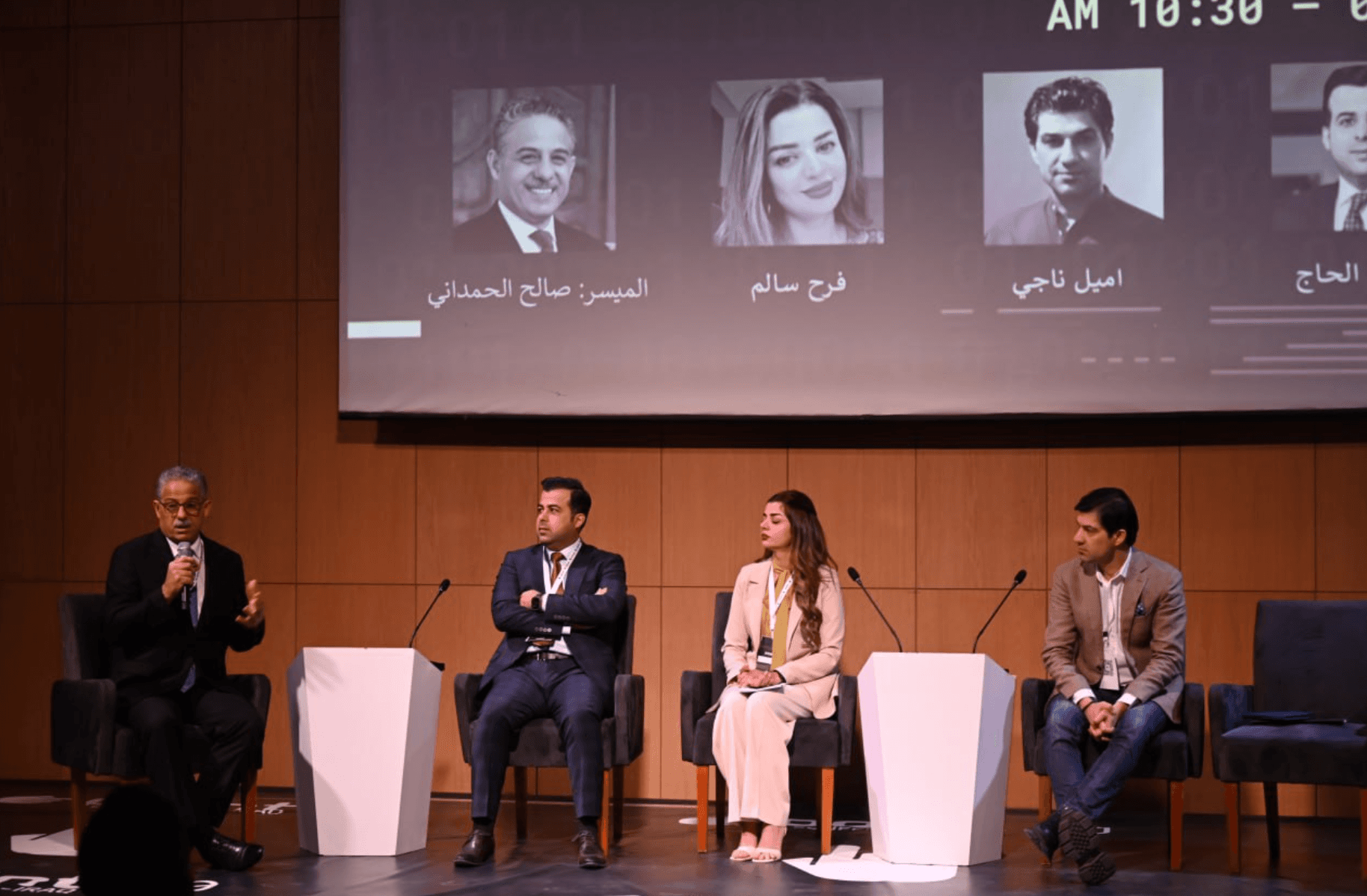

Content Crime: Freedom of Expression or Content Contrary to Public Morals?

September 16, 2023

Saleh: After a period of waning interest in or neglect of the issue of debased content, which initially garnered widespread attention, the topic remains highly controversial and rife with substantial information. Some suggest that the initiator of this was not the government or specifically the Ministry of Interior, but rather a journalist who popularized this term.

It could potentially serve as a tool to restrict freedom of expression. As Richard Beil, who accompanied Bremer, said about entering Iraq, it was a tactical goal, and the primary goal was Saudi Arabia, with the grand prize being Egypt. Perhaps debased content also has a tactical goal - a "scapegoat" - while the primary target is journalists, and the grand prize is freedom of expression in Iraq.

Saleh to Ameel: There are severe penalties for debased content, with guidelines and classification in place for content, and a platform for reporting it. Is digital content truly in need of regulation? Does it require minimal governmental oversight or absolute freedom?

Amil: You mentioned earlier that some journalists wanted to draw us into the debate about debased content. These journalists were advocates for the Eastern Gate, and now they are advocates for the digital gate. They're attempting to replicate the experience of the ideological campaign from Saddam's regime. As journalists and governmental authorities, we must differentiate between critique and criticism. It should be understood that critique doesn't imply enmity; its purpose is evaluation.

The Iraqi Penal Code is legislation from the 1970s, and the term "public morals" within it requires updating. We're not in the realm of defense; we're in the realm of clarification. As for absolute freedom, it doesn't exist in any field.

Saleh to Hussam: Legal experts often say that civilized countries legislate for everything, even for animals. In a country like ours with a significant amount of content, why do we object to establishing laws to regulate content that significantly affects society? Does Hussam Al-Hajj support enacting such laws?

Hussam: There's a principle that says any law not aimed at regulation is aimed at restriction. Freedom of expression is one of the fundamental pillars upon which democracy in Iraq, especially after celebrating yesterday's International Day of Democracy, is supposed to be built.

The issue isn't subject to personal preferences or dislikes but to a social contract—the constitution—then regulated by laws and clarified through guidelines. There's something called legislative impact assessment, and when we place the law in its framework, its importance or lack thereof becomes clear.

In Iraq, laws undergo mixtures. What's stated in the Penal Code doesn't align with the Constitution and what's mentioned in Article 38 of it. Articles 403 and 226 of the Penal Code contradict the Constitution's text. Similarly, the term "insult": does exposing corruption of a government employee constitute an insult? We need further clarification and definitions of these terms.

Saleh: Is there a systematic plan from political parties to restrict freedoms for journalists, bloggers, and platforms, or is it just a reaction to events that have occurred?

Hussam: Certainly, there is a plan and vision to restrict freedoms, to define what relates to the rules of engagement. Hence, we must pay attention to loose terminology in legislative texts. For instance, the term "public morals": these morals differ between Baghdad and Sulaymaniyah versus Karbala and Najaf. In one, girls might walk the streets wearing jeans, seen as acceptable, while in another, it might be considered against public morals.

"Offending modesty" is another issue. It could be categorized when someone uses offensive language, but it shouldn't hold accountable someone for wearing a particular shirt and being labeled as offensive to modesty.

Saleh: The term "terrorist" in Iraq can't be clearly defined, so how can debased content be defined? Democracy can't exist without secularism.

Saleh to Farah: This law has two sides. The first opens avenues for citizens to report, akin to Shatha Hassoun winning "The Voice," bringing joy to the Iraqi people. The second divides journalists and media personnel into opposing sides: one proposes combating debased content, the other opposes it. The question is, how do you assess the social responsibility held by both the citizen and the journalist?

Farah: One of the most famous phrases is "Your freedom ends where others' freedom begins." Therefore, we must know what is meant by "others' freedom": is it abstract or tangible? I believe that if what I write causes harm to an individual rather than an idea, my freedom has caused them harm. Hence, it's their right to deal with me however they see fit. However, if I'm speaking about ideas and I'm arrested or excluded because the idea doesn't align with a specific mood, ideology, or particular notion, then the case of others' freedom collapses. It's because confusion about what constitutes debased content and the surrounding ambiguity is exploited. This ambiguity and vagueness signal danger.

Social media, initially for socializing, has evolved into a platform for sharing ideas, news, sometimes by amateurs and professionals without censorship. The question here is whether these platforms are ready for this evolution, especially considering that our media has been directed and broadcasted specific ideologies for years. I don't believe we were prepared to receive such a large volume of content. Hence, we need content regulation. However, even the term "content regulation" is broad, so we must develop specific ideas to protect freedom of expression simultaneously.

Saleh: How responsible were citizens through reporting, and journalists regarding their social responsibility?

Farah: Citizens contribute significantly. When I find someone who disagrees with my beliefs, I go to a platform and advise my acquaintances to report them too.

Saleh to Ameel: If content remains unregulated and reaches all segments of society, creating shallowness among youth, especially girls, for instance, where they're raised to be wives, mothers, and professionals, but on social media, they're only taught to be influencers, is there importance in regulating these matters by authorities, or should things remain as they are?

Ameel: The story of restricting digital content requires research and studies. For instance, content directed at children is seen as a cultural invasion because social media algorithms are linked to what they watch or don't watch. The second issue is related to hate speech and similar topics; we must study how to regulate them. Restricting freedoms now puts us between defending our freedom of expression and being accused of defending debased content. Why are cases adapted to Article 403 and not 404 in the Penal Code?

Saleh to Hussam: Dissenting voices have diminished, as have activists'. Those who want to maintain their profiles now publish about climate, desertification, Saudi leagues, while critical issues have faded from the opinions of influential individuals. Could this be related to debased content and the campaign against it?

Husam: I want to ask, are we having a pre-state dialogue to establish the rules of engagement, or is there a state where the discussion revolves around whether the law aligns with constitutional legality? If the legislative authority complies with issuing a law that doesn't align with constitutional legality, then this authority should be held accountable. The political mood seeks to repeat the matter and restrict freedoms, deviating from the constitution. This means that the social contract has been disregarded. The constitution, particularly in Article 38, is clear that freedom of expression doesn't require a law to restrict it. When I criticize a minister's performance, I don't hurl accusations at them, as defined by the Penal Code for someone who attacks a government employee with false accusations.

There's a complacent elite; opinion leaders, unfortunately, often aligned with the authorities, especially during the al-Kadhimi era. Some have chosen positions within the authority, while others have opted for silence. Now, only the youth remain confronting the political mood that seeks to restrict.

Ameel: The spokesperson for the Interior Ministry, Khalid Al-Muhanna, stated in a televised statement that there's a significant audience supporting the debased content campaign. However, when there are 100,000 reports against an individual with more than 3 million followers, how can he claim massive support for the debased content campaign?

Saleh: This way of thinking isn't suitable for running the country. It's disjointed. Baghdad has everything. If you're surprised by certain trends, there are entertainment spots, and the country's culture continues. The harm doesn't lie in my children watching "Hassan Sajma." What worries me is the internet that exposes my son to the wider world. Countries aren't brought down by a dancer or a "hero."

Freedom of expression is receding. It was better five or ten years ago. Look at who's offering solutions now and who was offering them ten years ago? It used to be in the hands of the older generation. Yes, we criticize them for aligning with the Americans, but now the solutions are in the hands of those who lack experience.

Trust that those responsible for combating debased content are fundamentally unqualified. Some can't read or write. They couldn't even evaluate "Aboud Skiiba," who's entertaining in his jokes and English language use. How can they evaluate religious figures, preachers, intellectuals, poets, and singers?

Saleh to Farah: How much responsibility lies with journalists in promoting the fight against debased content, given that they might have contributed to inflating this content?

Farah: I didn't intend to answer this question, but frankly, political money is dominant. Citizens distinguish between politically driven writing and impartial writing. Politically driven writing exploits its tools and power to label things as debased content, claiming certain content "threatens national security or civil peace," but in reality, it enforces what it promised to deliver in return for that power.

Our fundamental problem is ignorance—the society's ignorance of its rights. Not all citizens are aware of their rights. If an incident occurs in Karbala, citizens might not know whether it was a violation or a lawful action. The responsibility to clarify this lies with journalists, and this is where the danger of politically driven writing lies.

Interventions:

Beishdar to Ameel: Initially, you said there's no freedom of expression. However, protesters reached the parliament gates, and if we compare Iraq's freedom of expression to neighboring countries like Turkey and Iran, Iraq is better.

Hussam responds: I say there's no freedom of expression, and here's the evidence. I can't post about an armed group; I'd be killed. I can't talk about them on screen; I'd be killed. We can't produce a film or a play criticizing the uncontrolled arms; we'd be killed.

"Dlovan: If a state grants freedom of expression but cannot protect that freedom, it falls short as if it were suppressing it. Is it logical now to classify this content as derogatory or not derogatory? What's the standard? Perhaps I'd like to see joke content. Would that be derogatory? What's the legal basis?

Ali Al-Habib: Our problem in Iraq is the emotional public and the lack of awareness, which the government capitalizes on. There's a significant issue between religious sentiments and religious figures. Also, the question arises: are public morals religious or societal? If they're religious, Iraq is multi-religious, and if they're societal, Iraq is also diverse in this aspect. How can we define offense within a legal framework?

Participant:

Freedom of expression is one thing, and content conflicting with morals is another. Why does the government say the content is against public morals while massage centers from Erbil to Baghdad have immoral activities inside, and the government grants them licenses?"

"Israa Al-Salman:What's the standard for derogatory content? When we visit accounts like Taysir's and others with millions of followers, it represents society's taste. Why aren't nightclubs, where underage dancers are present and trade occurs, classified as derogatory content?

And if Amal Al-Fahad, who introduced a political figure at Gulf 25 by car, gets banned, young people will seek similar content in other countries. What's the solution then? Will we shut down the internet?

Amil: Freedom of expression is an inherent individual right, and it's the state's responsibility to safeguard and protect it, not a favor from them. Regarding derogatory content, in winter, we see children playing in contaminated water; isn't this derogatory content due to lack of services?

Farah:There should be standards, tools, and skills in the society to distinguish between what's beneficial and what threatens social peace.

Hussam:Regulating freedom of expression begins with law enforcement, followed by establishing institutions that restore the state's authority.

Saleh:Freedom of expression needs a democratic country to be applied in, and democracy needs democratic parties. Parties that still believe in 'the tough guy' aren't fit to govern.

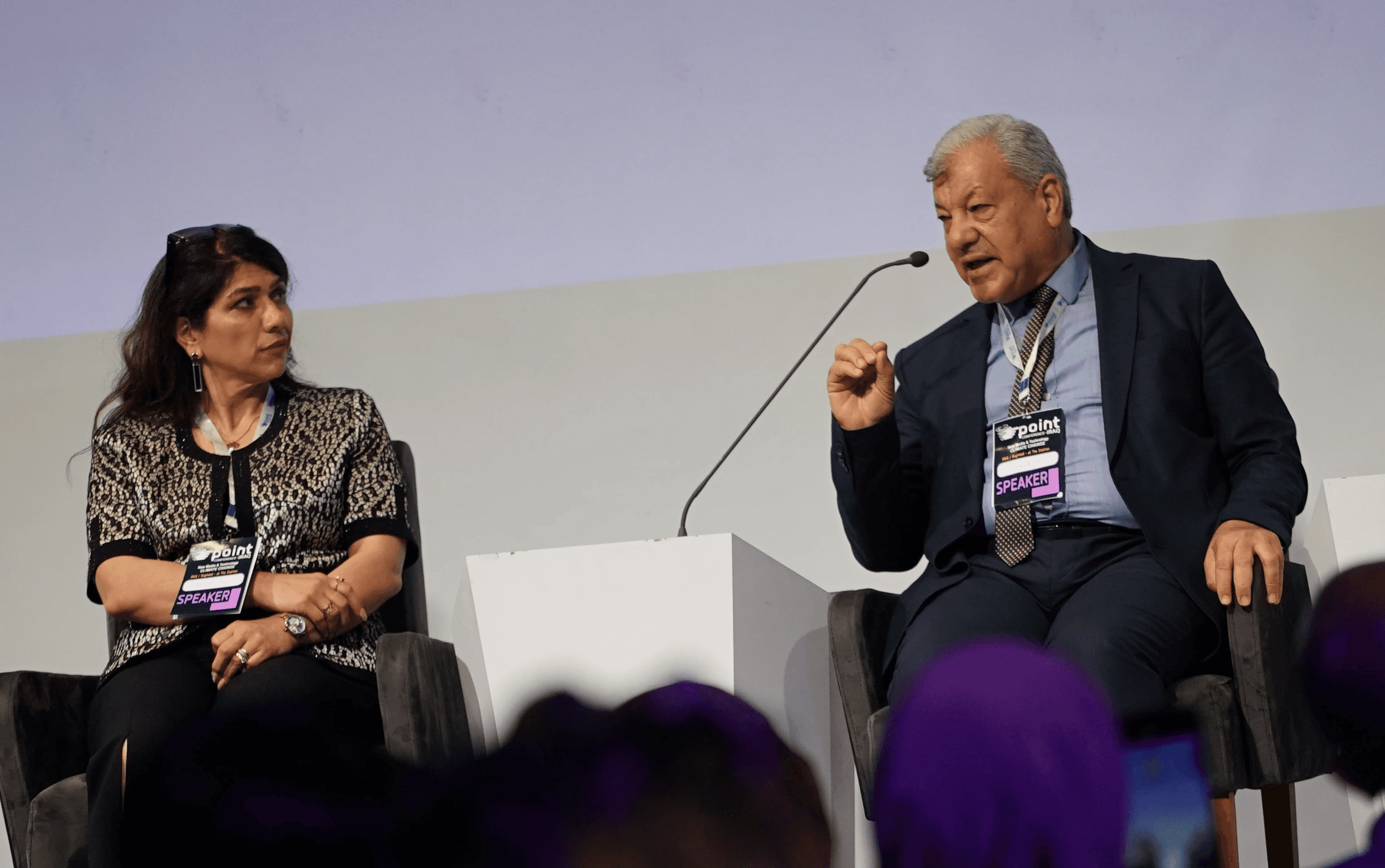

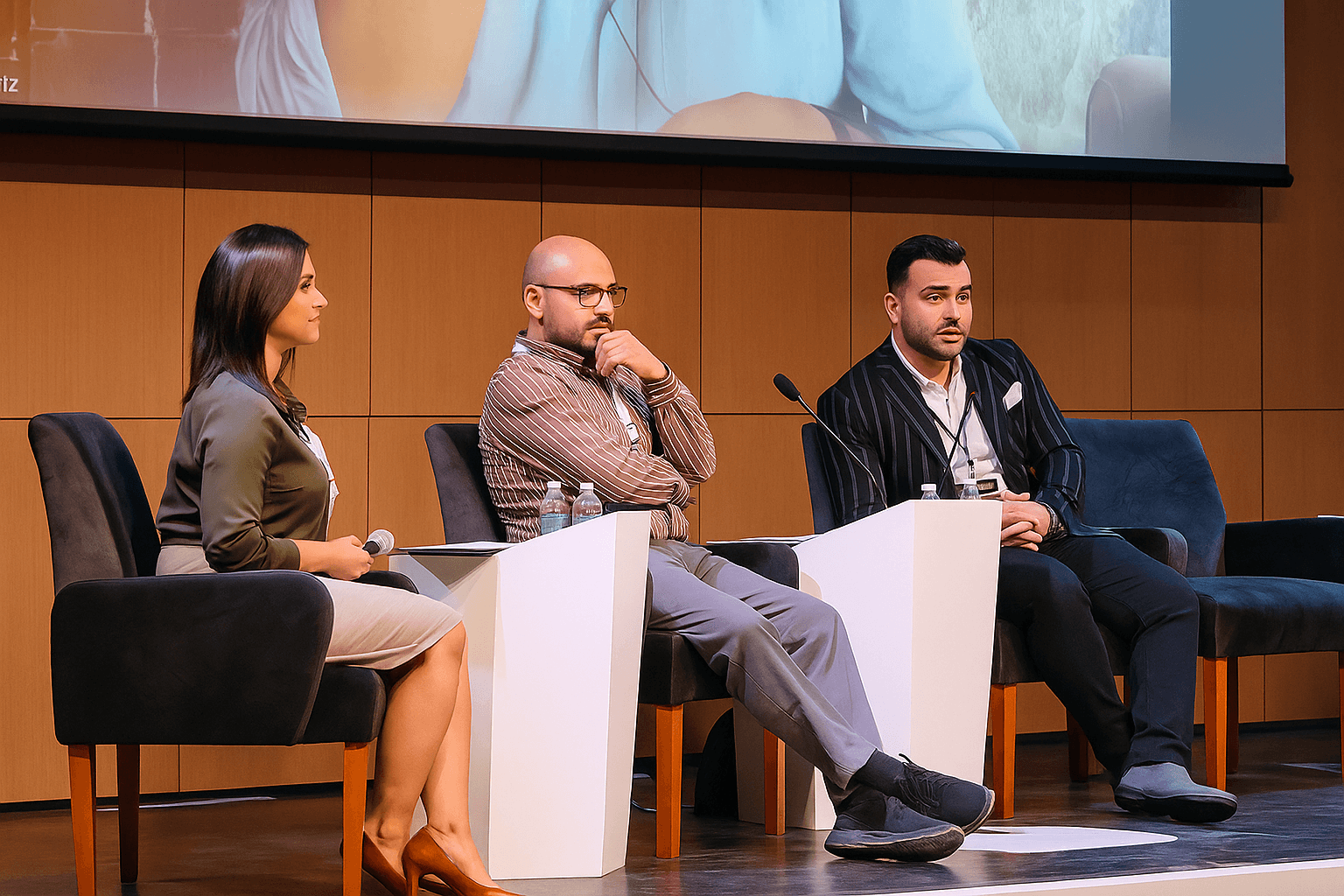

Gallery

Memories from past Events

Content

FAQ

Frequently Asked Question

I have a question

When and where will the next conference take place?

The conference will be held on June 24–25, 2024 in Sarajevo at Dom Mladih.

Who can attend the conference?

How can I register to attend?

Will the conference be live-streamed?

Partners

Tawasoul Organization for Youth Empowerment · Iraq – Baghdad – Karradah city

+964 770 790 6400

Tawasoul Organization for Youth Empowerment · Iraq – Baghdad – Karradah city ·

Mobile: +964 770 211 1332

Copyright©2025.Pointiraq. All Right Reserved.